Ah, MV Agusta. The name alone sounds like a Shakespearean tragedy or a particularly fancy pasta dish. But no, it’s one of the most iconic motorcycle brands in history—a brand that combines speed, style, and a healthy dose of Italian flair.

If motorcycles could talk, MV Agusta (as in Meccanica Verghera Agusta) would be the one wearing a leather jacket, sipping espresso, and dramatically gesturing about the meaning of life. Let’s dive into the history of this legendary marque, where passion, performance, and a touch of chaos collide.

Act 1: The Birth of a Legend (1945)

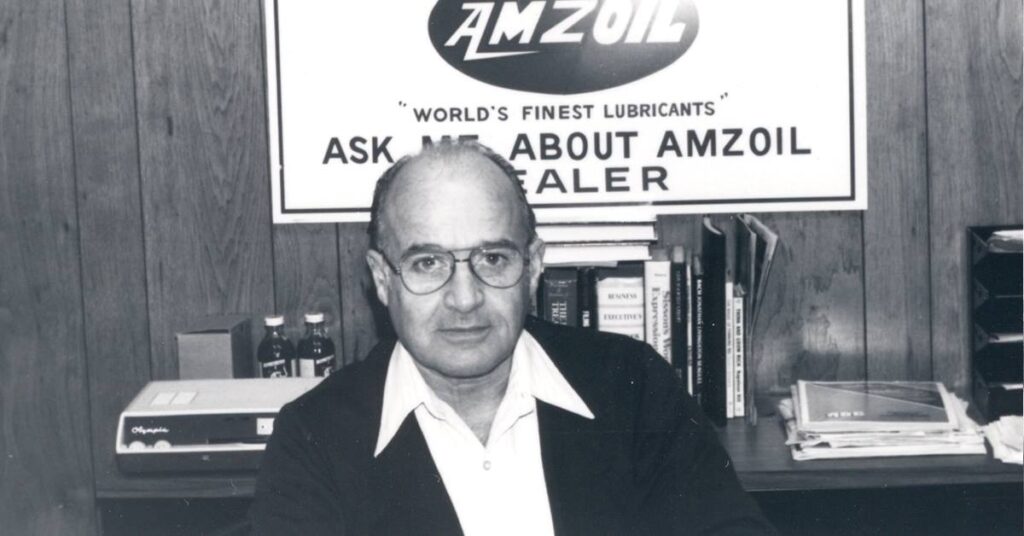

Our story begins in the aftermath of World War II, a time when Italy was rebuilding itself and Count Domenico Agusta was looking for something to do. You see, the Agusta family had been in the airplane business, but post-war regulations said, “Hey, maybe let’s not build warplanes anymore?” So, Domenico did what any sensible Italian aristocrat would do: he pivoted to motorcycles. Because nothing says “rebuilding a nation” like two wheels and a screaming engine.

On January 19, 1945, in the town of Cascina Costa (near the Malpensa airport near Milan), a private company, Meccanica Verghera S.r.l., was registered.

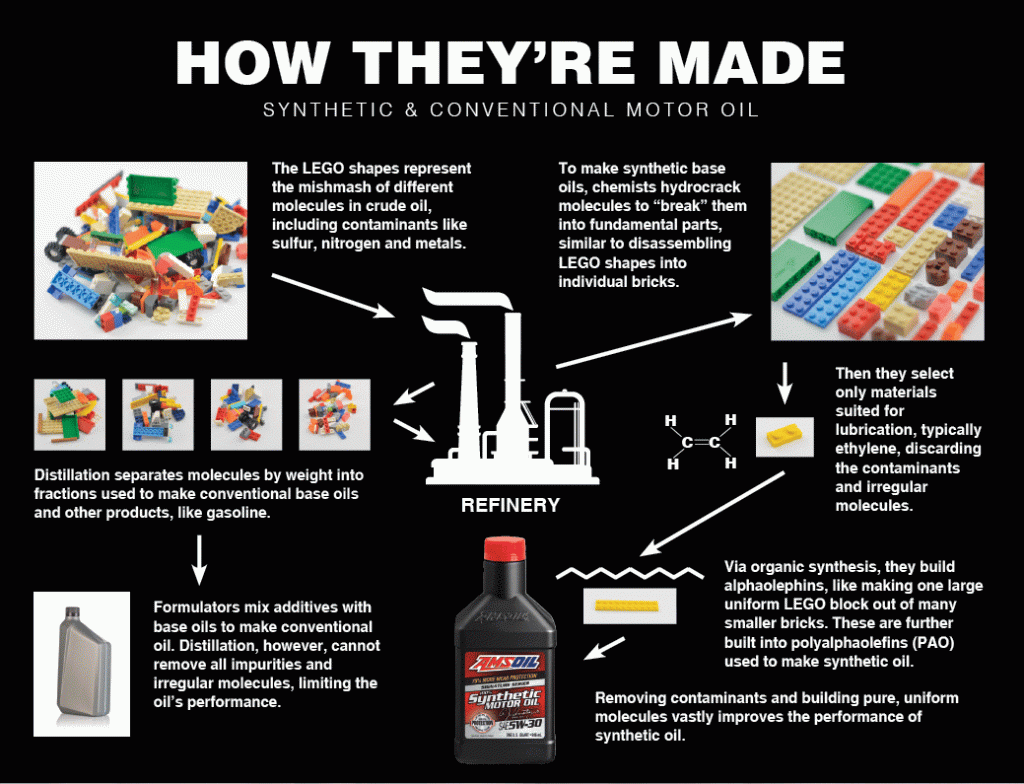

The first MV Agusta bikes were humble, utilitarian machines designed to get Italians from point A to point B without breaking the bank.

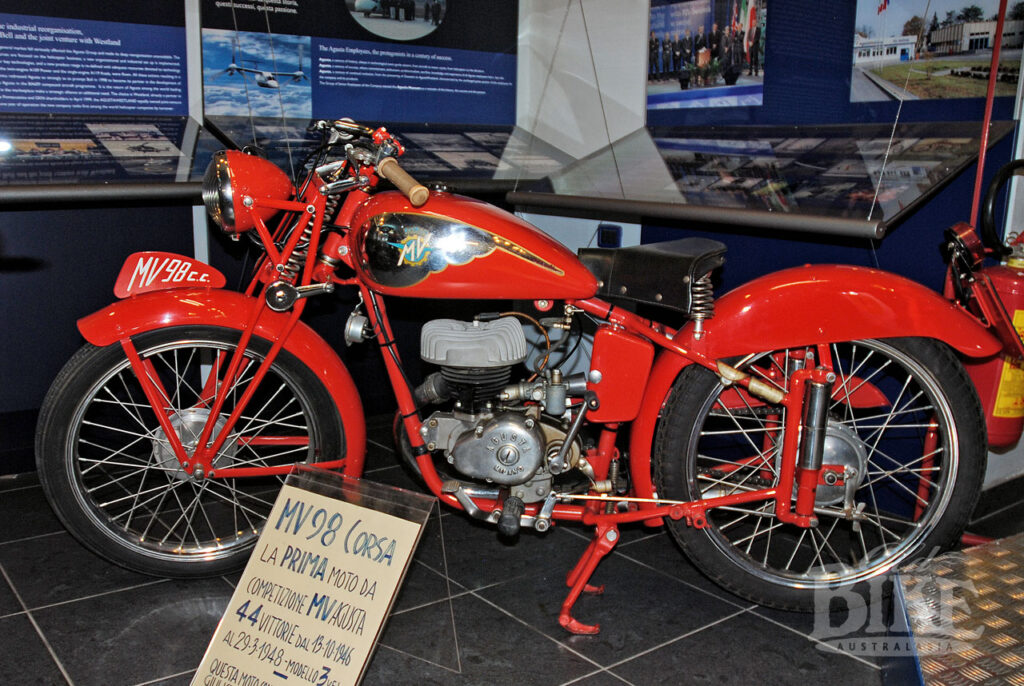

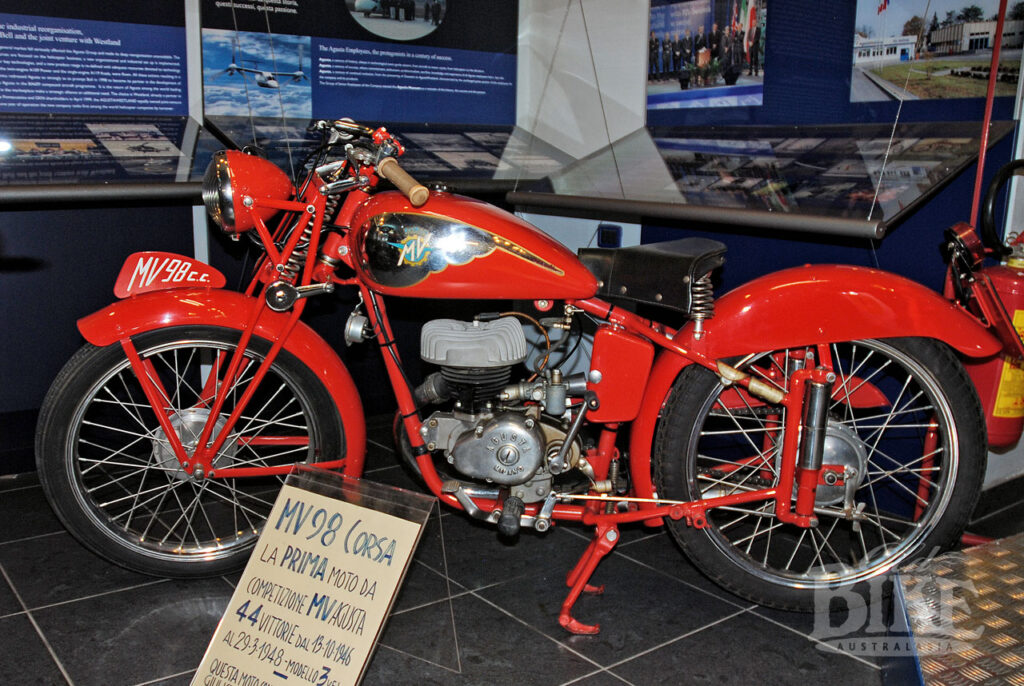

Using an engine that had been prepared by August 1943 which was a 98 cc single-cylinder two-stroke with a two-stage gear box, and spare parts obtained from the black market to bypass shortages, a prototype motorcycle was constructed. The prototype was exhibited to the press in late October 1945 at a dealership on Via Piatti in Milan. It was light motorcycle with a steel tube rigid frame, a girder fork, 19-inch wheels, and a gas tank marked with a large M and V. It was initially called “Vespa 98” before being renamed to “MV 98” to avoid confusion with the Vespa scooter produced by Piaggio.

The MV 98 was first produced en masse in 1946. Two versions were sold to consimers: Economica, based on the prototype presented a year earlier, and Turismo, distinguished by the presence of a three-speed gearbox and a rear suspension. The Turismo proved to be so overwhelmingly popular that before long, the Economica was discontinued. In 1946, about 50 units were produced.

But Domenico had bigger dreams. He wanted to race. And not just race – he wanted to win. Thus began MV Agusta’s love affair with motorsport, a relationship that would define the brand for decades.

Act 2: The Golden Era (1950s–1970s)

Count Domenico was likened to Enzo Ferrari. The Agusta family produced and sold motorcycles almost exclusively to fund their racing efforts. So soon after the start of production of its first model MV 98, the company launched its own factory racing program.

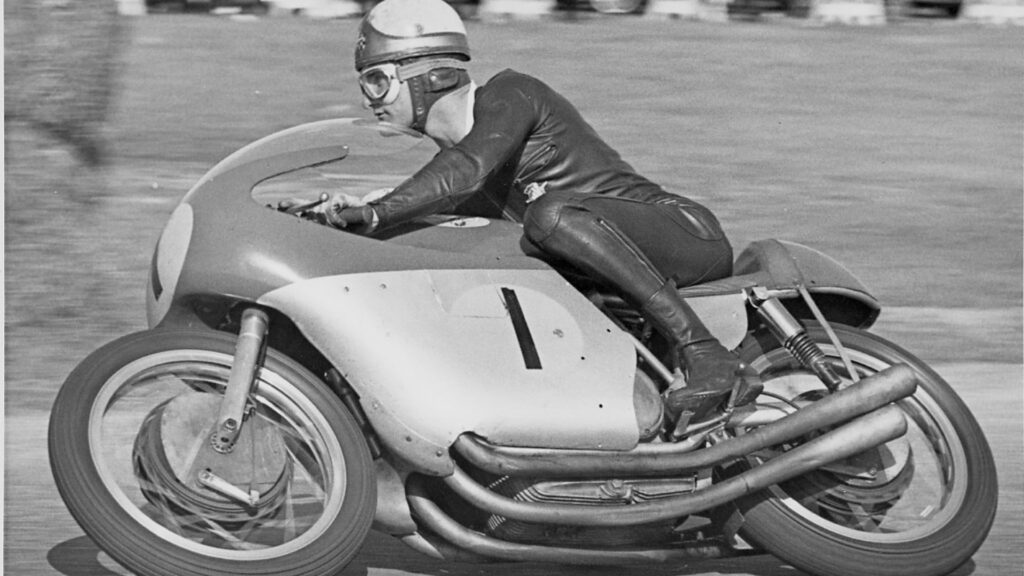

But here’s the thing: MV Agusta didn’t just win races—they did it with style. Their bikes were works of art, with sleek lines, vibrant red paint, and that iconic “MV” logo that looked like it belonged on a Renaissance painting. Even their engines sounded like opera singers hitting high notes. It was as if every bike came with a built-in soundtrack of Ennio Morricone music.

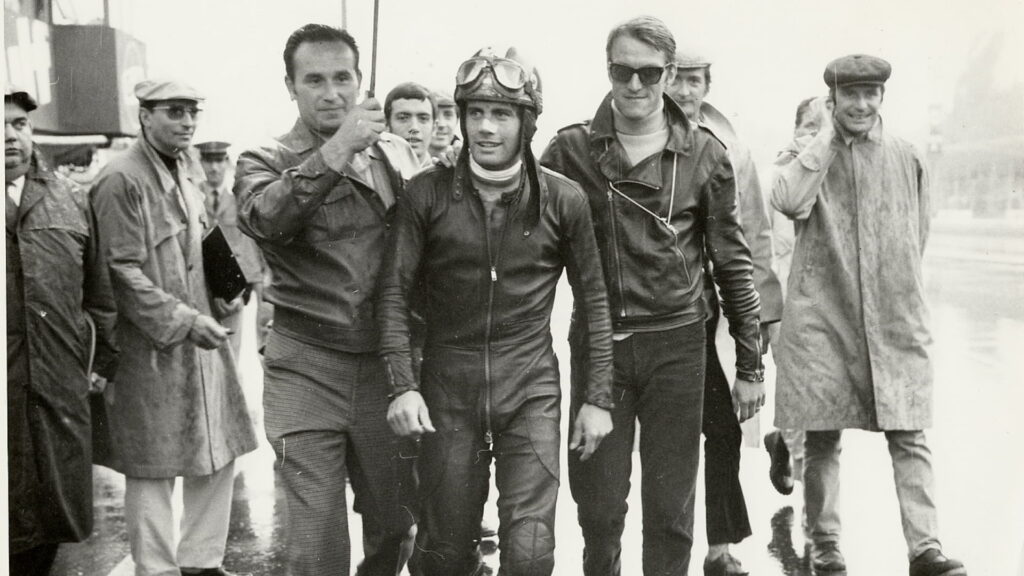

Vicenzo Nincioni delivered the brands’s first victory when he won the La Spezia road race on October 6, 1946. Just a week later, he took the third place in Valenza, where the first place was also taken by the MV racer Mario Cornalea. On November 3, in Monza, MV racers Vicenzo Ninconi, Mario Cornalea and Mario Paleari occupied the entire podium for the first time in MV racing history. It was the start of the MV Agusta dominance.

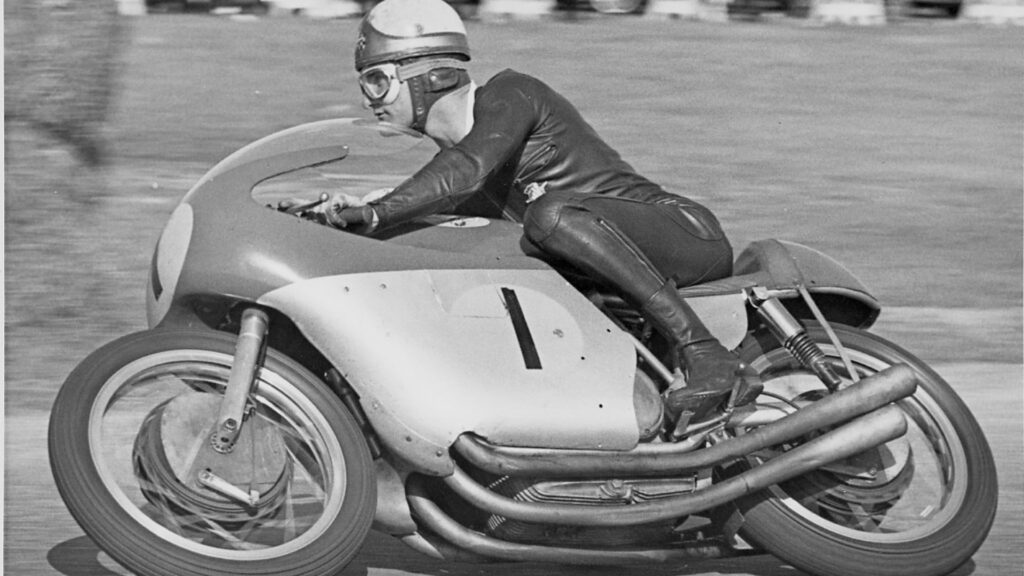

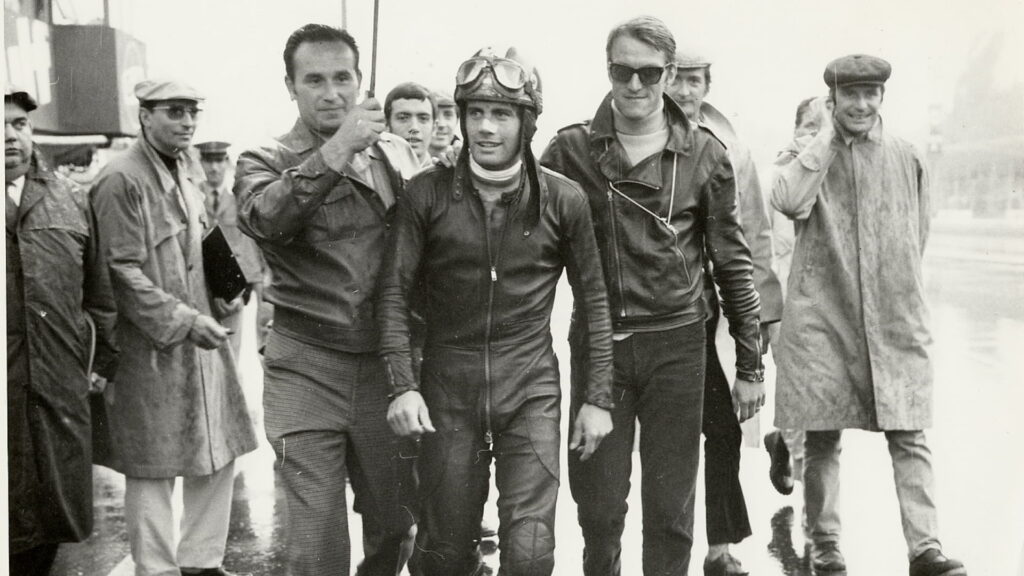

In 1961, British racer, Mike ‘The Bike’ Hailwood joined the Italian team. He also won the rode the 500cc four-cylinder MV Agusta racebike in its signature red and silver paint to several wins including the 1965 Tourist Trophy (TT).

And then, in 1965, an Italian racer by the name of Giacomo Agostini signed up to ride the factory’s three cylinder race bikes. He went on to win 311 races, 18 Italian championships, and 13 world championships, thereby cementing both his and MV Agusta’s names as legends.

So, if MV Agusta were a movie, this would be the montage where they win everything and look impossibly cool doing it. They won 37 World Championships, 270 Grand Prix races, and basically every trophy they could get their hands on.

End of Part 1

We shall look at the 70s and through to modern day in Part 1, so stay tuned!