We have written about fuel octane, or more specifically, what it does and why do we have different RON ratings at the pump. Fuel octane is directly tied to the engine’s compression ratio.

What is compression ratio?

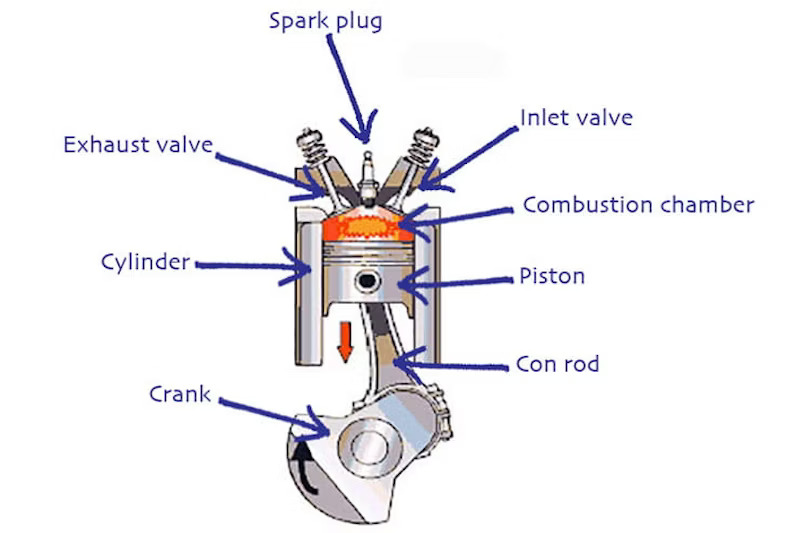

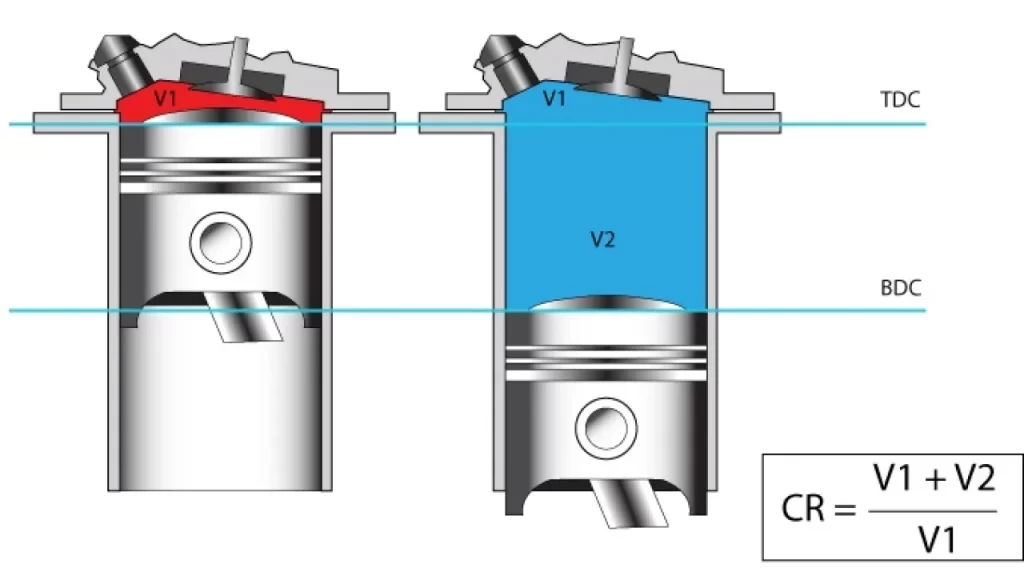

A ratio means something divided by another thing. Firstly, take the cylinder’s volume when the piston is fully at the bottom of its stroke (bottom dead centre/BDC), and add the combustion chamber’s volume. Secondly, take the volume of the cylinder when the piston is fully at the top of its stroke (top dead centre/TDC). Now take the BDC volume and divide against the TDC volume. This is why compression is expressed as 10:1. 11:1. 13:1 and so forth.

The higher the ratio means the fuel air mixture that enters the cylinder is squeezed into a much tighter space. Higher compression is good for making more power as more of the heat from combustion is transferred to kinetic energy in pushing the piston down.

Whichever way we go about it boosting the compression ratio is an easy route to more power. High compression pistons are in essence “bolt-on horsepower”. Modern bike engines tend to run compression ratios in the 10:1 to 12:1 region.

However, there is a limit

But there are limits to how high the compression ratio can go.

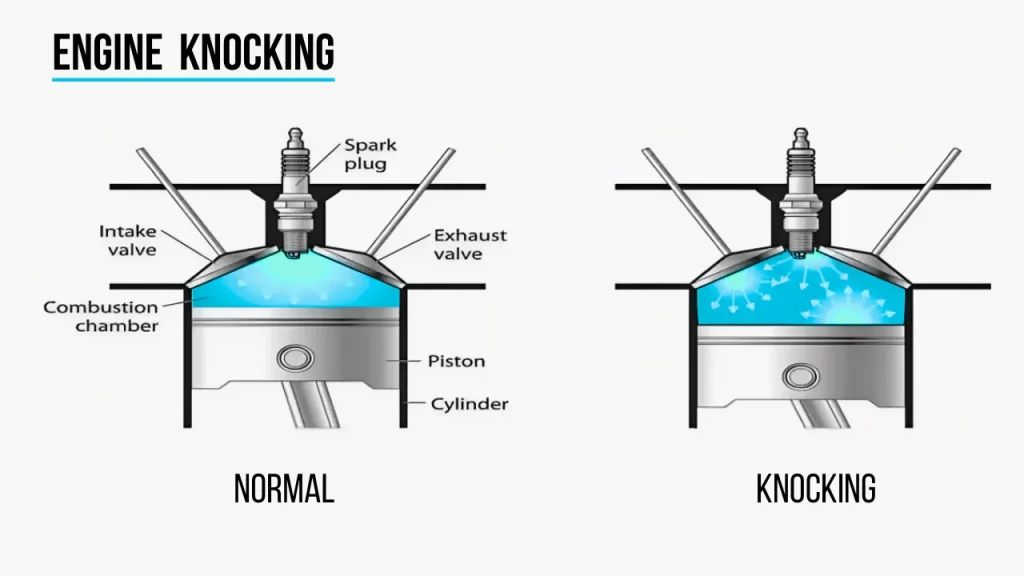

Any medium, whether is it just air or the fuel air mixture will get hot as it is compressed more and more. The higher the compression, the higher heat the medium will achieve. And, when the heat becomes too high, the fuel air mixture will self ignite before the spark plug ignites it at the correct timing.

This self-ignition sends shockwaves around the combustion chamber that can cause catastrophic failure. These shockwaves can be audibly heard and has a metallic knocking sound, hence called “knocking” or “pinging.”

In fact, diesel engines work this way. They employ very high compression ratios and compressed air alone until it gets really hot before diesel is injected into the combustion chamber. This mix causes instantaneous ignition. It is also why diesel engines produce that signature clacking sound.

So, how do we stop self-ignition? There are three methods: Lowering the compression ratio, retarding the ignition timing, or using fuels with higher octane rating. We shall explore this in another article.