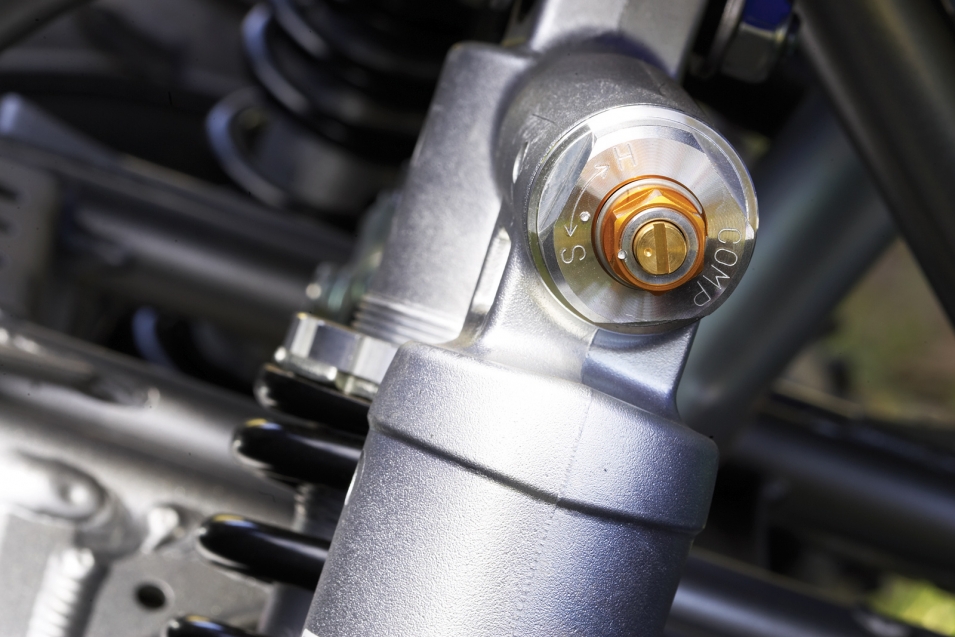

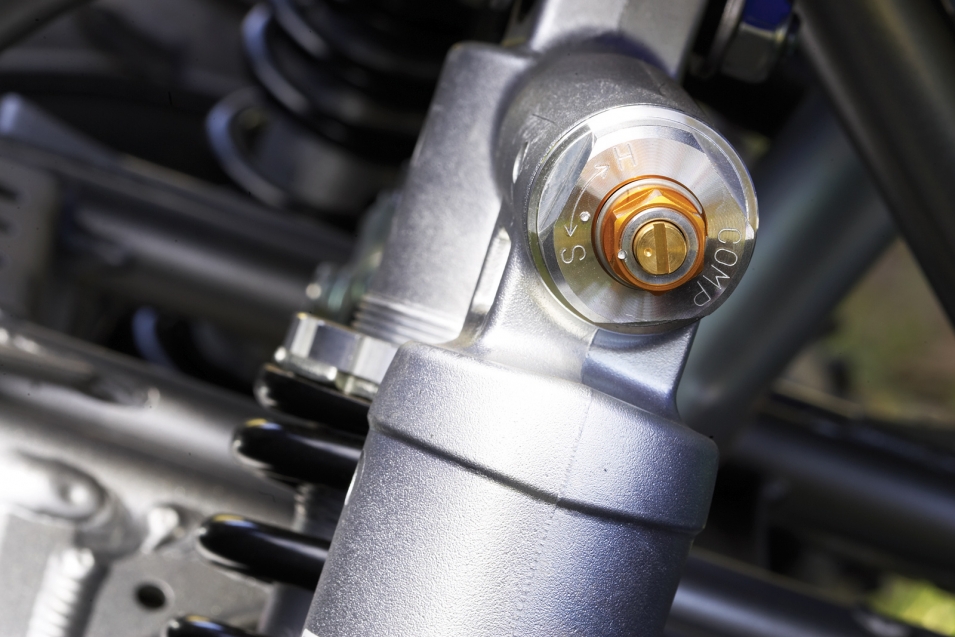

We provided a guide on troubleshooting preload adjustment and rebound damping previously. We shall deal with compression damping in this last part.

To recap, compression damping is opposite of rebound damping. It controls how quickly the wheel travels upwards when it contacts a bump in the road.

Think of compression damping as the resistance when the spring is squeezed.

So, there you have it.

Always “mark” the factory settings before you start and note them down. For example, turn the compression damping to fully minimum and count many clicks to get there. Then, turn it to maximum, noting the number of clicks. Finally, turn it back to the original position and start from there.

Our advice is to adjust one parameter at a time, say start with rebound damping before moving on to compression damping. Adjusting everything all at once will confuse you.

Another advice, do not go to the maximum unless you really, really need to (for example poor quality forks). Having a little less of something may actually gain you more in terms of enjoyment.

Lastly, please do not think you need to add more preload/compression/rebound just because you ride faster. You can do so at the track but that does not necessarily mean going all the way to the maximum. Conversely, adjust what is necessary to allow the bike to work for you, not vice versa.

Suspension technology has progressed by leaps and bounds over the years. The motorcycle started out as a little more than an engine stuffed into a bicycle frame, hence the only suspension was the rider’s bum and his resolve to withstand the hammering.

Since then, motorcycle suspension evolved into simple underseat springs to sprung struts to hydraulic and gas damping to electronic self-adjusting marvels.

Regardless, the principles of the suspension remain the same. There are a number of parameters that govern how your bike behaves whether on the road, track or off-road. However, only three parameters are adjustable on a motorcycle (without further modification), namely preload, compression damping and rebound damping.

Adjusting the suspension best requires a bit of background knowledge, because whatever adjustments that may have you feeling right may not be exactly right for the bike’s dynamics. A wrong adjustment may mask itself as another problem, causing you to go around in circles. Oh yes, we’ve been there.

We’ll discuss one topic per week. We’ll also speak to the experts on aspects of suspension technology, adjustments and modifications, while dispelling some myths along the way.

Hope this series will be beneficial to all our readers.

Any discussion about suspension has to start with preload. Preload is of course related to spring rate, but since most riders don’t change the springs in their suspensions, we’ll just stick to preload.

To put it in simple terms, preload means the amount the springs are compressed when the suspension is fully extended.

For illustration purposes, take a valve spring and stand it on your desk. Now add some weight to the top so that it compresses a little. That’s preloading the spring. Adding more weight means adding more preload, while taking some off means reducing preload.

When you increase the preload by turning on the preload adjuster on the forks, or collar on the rear shock, suspension sag is reduced; and vice-versa. The spring pushes back against the adjuster collar, lifting that end of the bike up. So, if you increase (by turning clockwise) your rear suspension’s preload, the seat goes up higher, and similarly for the front.

Therefore, adjusting the preload DOES NOT change your spring rate. If someone comes up to me and say I’d make the spring stiffer by adjusting the preload… well, I’d tell him to go fly a kite. But that’s just me.

We’ll leave this subject here. More on this in latter instalments.

If a bike’s suspension depends on the spring along, it can leave itself prone to oscillations. A compressed spring stores kinetic energy. When it’s released, it may extend to more than its resting length. The load on top of the spring has now received this kinetic energy and unleashes it back downwards, compressing the spring. This goes back and forth until that kinetic energy is transformed to heat (absorbed in the shock absorber’s oil).

Have you ridden on a bike that “pumped” up and down or wallowed like a sampan in stormy seas? (My bike does that.) Yes, it’s due to the lack of damping.

Damping is divided into two: Compression damping and rebound damping.

Compression damping (or just compression) determines how fast the wheel move upwards when it contacts a bump. Correct compression damping will allow the suspension to absorb bumps and road irregularities better.

With more compression dialed in, the suspension, hence the wheel, is more resistant to moving upwards and vice-versa. Dialing in the correct amount will also deal with fork dive to a certain amount during hard braking, although that depends more on the spring rate and preload.

Too much compression damping will cause the shock of the bump to be transferred directly to the chassis and rider. (That “BLAM” feeling when you hit a bump.) Consequently, the wheel will skip across the bumps, or cause the brakes to lock up easily as the suspension resists being compressed.

On the other hand, too little will have the wheel kicked up quickly, which will also cause it to lose touch with the road. Hitting corners at high speeds will cause the suspension to “squash” down, reducing ground clearance.

Rebound damping is the opposite of compression damping. Rebound determines how smoothly and controlled the suspension re-extends to its proper state, after it has been compressed.

Without or too little rebound damping will cause the spring to re-extend quickly, or in simple terms, bounce back. The rider will feel as if he’s being kicked out of the seat after the initial bump has been absorbed. It’s like squeezing a spring between your fingers and letting it go abruptly, or like a Jack-in-a-Box.

Too much rebound damping will cause the wheel to “pack up.” That means the wheel will only come back down too slowly, causing the bike to feel “loose.”

That’s it for this week. This is just basic knowledge. We’ll touch on more next week, so stay tuned!

© Copyright – BikesRepublic.com 2023 Trademarks belong to their respective owners. All rights reserved