Kami suka motosikal replika perlumbaan. Kami lebih menyukai motosikal replika perlumbaan yang rare (jarang ditemui). Kami mungkin sanggup melakukan yang luar biasa untuk mendapatkannya, walaupun terpaksa makan ubi kayu sahaja sepanjang hayat kami. Keghairahan sebegini sukar difahami oleh ramai orang tetapi, lihatlah Yamaha YZF-R1 Jonathan Rea Replica ini dan anda akan faham mengapa.

Ia sempena perpindahan Jonathan Rea ke Yamaha dari Kawasaki. Juara WSBK enam kali itu membuat langkah mengejutkan bermula musim tahun ini, selepas juara 2021 Toprak Razgatlioglu mengosongkan tempat itu. Rea pasti telah melihat kekuatan R1 di tangan Toprak apabila menewaskannya pada musim itu.

Yamaha YZF-R1 Jonathan Rea Replica bukan sekadar cat yang anda boleh dapatkan di kedai berhampiran. Sebaliknya, terdapat begitu banyak barangan prestasi di bawahnya. Ini termasuk sistem ekzos Akrapovic, roda aluminium tempa Marchesini, kit kartrij fork Öhlins TTX, monoshok belakang Öhlins NIX dan peredam stereng boleh laras.

Anda juga boleh menaik taraf brek hadapan kepada kaliper Brembo GP4RX dan cakera T-Drive, dengan harga tambahan, sudah tentu. Pilihan lain ialah Pek Garaj yang merangkumi kaki hadapan dan belakang GYTR, tikar motosikal, dan penutup motosikal Jonathan Rea tersuai.

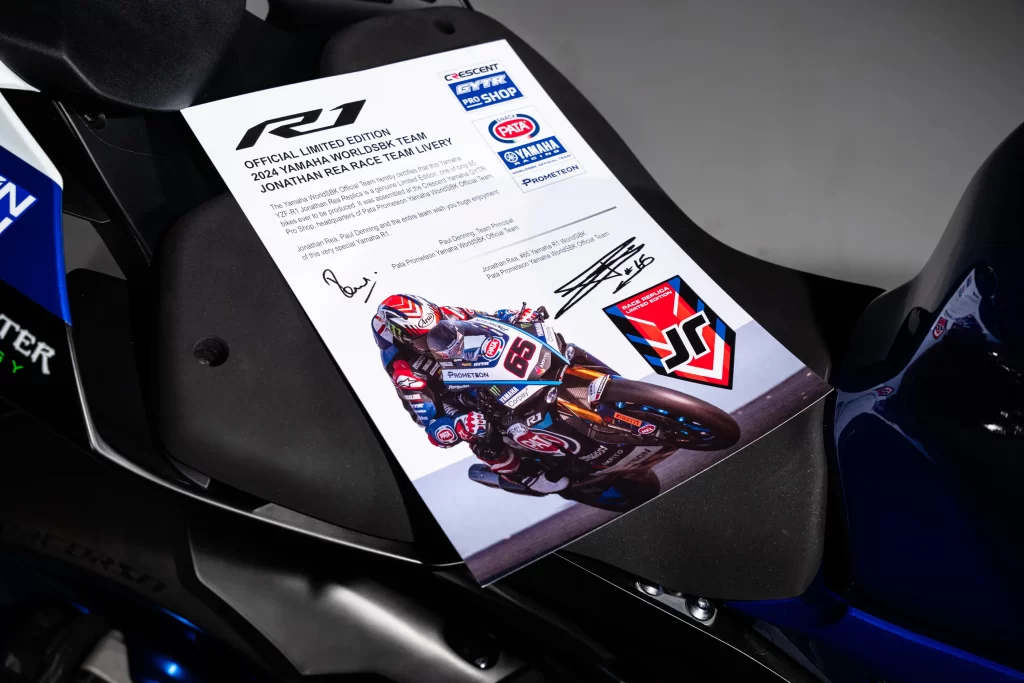

Crescent Yamaha mengatakan bahawa Yamaha YZF-R1 Jonathan Rea Replica tersedia untuk penghantaran ke seluruh dunia. Terdapat hanya 65 yang akan dibuat, sepadan dengan nombor perlumbaan Rea. Anda hanya memerlukan £29,995 dan ia akan menjadi milik anda. Oh, ia juga ditawarkan dalam warna Winter Test.

Satu lagi perkara yang menjadikan replika ini sangat istimewa kerana tahun 2024 adalah tahun terakhir produksi jalan raya untuk Yamaha YZF-R1.