-

The latter part of the 1990s saw more advanced motorcycles.

-

Some of the innovations are still in use today.

-

Sportbikes still took the lead.

We stopped at 1994 for Part 1, so we will finish the decade in this Motorcycles that Defined the 1990s — Part 2 feature.

The bikes in the latter parts of the decade began to look like the current ones as the technologies learned through the 1970s and 1980s were applied correctly. Innovations such as twin-spar aluminium frames, dual disc brakes, electronic fuel injection and ignition, ABS et al were becoming a common denominator.

But sportbikes still led the way as the alpha bikes.

Click here for Motorcycles that Defined the 1970s.

Click here for Motorcycles that Defined the 1980s – Part 1.

Click here for Motorcycles that Defined the 1980s – Part 2.

Click here for Motorcycles that Defined the 1990s – Part 1.

Yamaha TZM 150 (1994)

The TZM 150 was set to rule Malaysian roads and put Yamaha squarely back into the 150cc two-stroke leadership. Its YPVS-equipped engine was rated at 35 bhp, but it was enough to push the lightweight bike to 208 km/h! Besides that, it had a brutal acceleration that rivalled the four-stroke superbikes. But it had a superbly light handling to match.

It was unfortunate that The YPVS valve itself was the weak point, usually breaking at one end of the spindle that limited its sale in latter years.

This writer still gives any good-looking TZM 150 a wide berth today, unless he’s riding a 1000cc superbike.

Aprilia RS250 (1995)

Many would remember this bike fondly. In fact, it had the fierce reputation as superbike killer. Why not, with 72.5 bhp carrying only 167 kg wet, it would blow the four-stroke superbikes into the weeds.

Its 249cc, two-stroke, liquid-cooled, 90-degree, V-Twin engine was sourced from the Suzuki RGV250. So much so, it was sometimes called the RSV250. Aprilia added the technologies learned in GP racing (ridden by the likes of Loris Capirossi, Tetsuya Harada, Max Biaggi, Valentino Rossi) to the bike. The engine was given a revised ignition ECU, different exhaust expansion chambers, cylinder barrels and airbox. The 32mm flat slide carburettors were retained.

The RS250 was one of the first road bikes to feature an instrument cluster with an LCD screen displaying rev limiter warning, coolant temperature, chronometer that memorises 40 fastest lap times, among others.

Beginning the 1998 RS250GP1, the brakes were high grade for the time consisting of dual Brembo Pro (Gold Line) calipers gripping on 298 mm discs at the front.

The Aprilia RS250 is still worth a lot of money today. Good examples can cost more than the original 1995 price.

Kawasaki Ninja ZX-6R (1995)

Responding to their competitor, Kawasaki was the last to introduce a 600cc sportbike. The Ninja ZX-6R was dressed in the fairing derived from the 1994 Ninja ZX-9R and had ram air induction, as well. The inline-Four engine produced 105 bhp, making it the most powerful 600cc sportbike (before the term supersport) was coined.

The model would go on to feature a 636cc engine in 1998 for the road going version, until today.

Honda Wave (1995)

We have to include this one. The Wave has been around for 24 years! The Wave was the successor to the insanely popular Cub but the latter was in production for many years after it was stopped in other countries.

The Wave was offered in 100-, 110-, 125- and 150cc variants. Malaysia received the 150cc version which was actually a modified version using the 57mm racing block. Yes, we actually had a factory race bike!

The Wave is still sold until today, but the RS150R took over as the “sporty” model.

BMW R1100RT (1996)

Ah, the grandaddy of the current R 1250 RT. The R1100RT was BMW’s sport-tourer for many years until the advent of the S 1000 XR. The current RT is repositioned as a luxury sport-tourer, instead.

The R1100RT used the same Oilhead Boxer of the R1100GS and R1100RS. The suspension setup also took on BMW’s trademark Telelever front and Paralever rear.

It became really popular as a bike to chew down the kilometres while being able to carry a lot of payload — at 205 kg — on top of its 285 kg ready to ride weight.

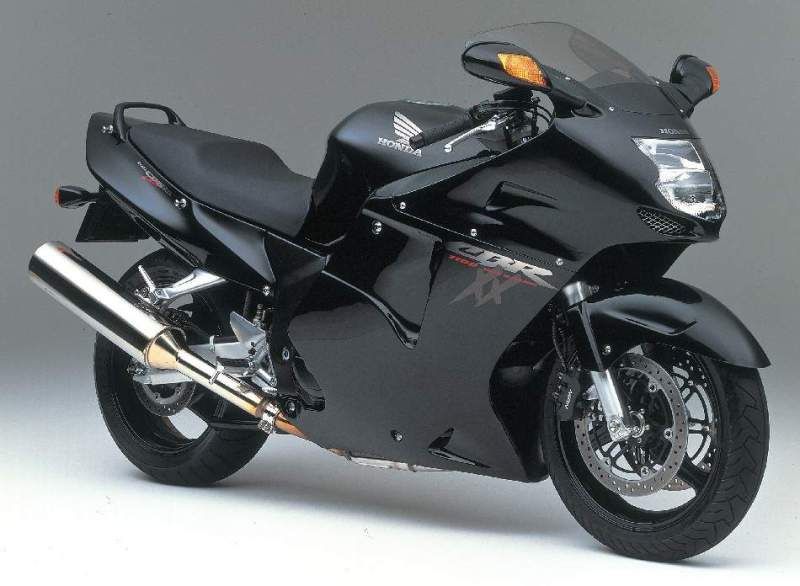

Honda CBR1100XX Super Blackbird (1996)

The CBR1100XX was built specifically to challenge the Kawasaki Ninja ZX-11 for the fastest production motorcycle crown. Its Super Blackbird name was a tribute to the Mach 3.8 (4692 km/h) Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird spyplane.

There was a lot of bruhaha surrounding the launch of this bike, with the manufacturer claiming to be the first to hit 300 km/h. It didn’t. It only hit the fastest of 287.3 km/h when tested by Sport Rider, but it was enough to beat the ZX-11’s 281.6 km/h.

We wrote about this bike at length in the 15 Fastest Production Motorcycles of All Time feature.

Suzuki TXR150 (1996)

The TXR150 superseded the popular Panther in Malaysia. It received a revised headlamp fairing here, while getting a full RGV-like fairing overseas.

With 36 bhp on tap, it was one of the fastest bikes on Malaysian streets. Some modified versions were known to hit 200 km/h.

Its arch nemesis were the aforementioned Yamaha TZM 150 and Kawasaki KR-150 (KIPS).

Honda VTR1000F Firestorm/Superhawk (1997)

1997 was another bumper year for sportbikes, V-Twins in particular, driven by that Ducati 916.

The first was the Honda VTR1000F which surprise, surprise, featured a 996cc 90-degree V-Twin. But the bike actually feature a number of innovations in the quest to make it the premier superbike.

It was the first Honda to use the HMAS (Honda Multi-Action System) suspension. The engine was attached to the frame as a stressed member, with the swingarm attaching directly to the rear of the single-piece crankcase. The conrods were also cast as one piece. It also had split radiators placed in both sides of the fairing in order to locate the engine further to the front.

But strangely, Honda decided on carburettors — 48 mm ones, the largest on a production bike — instead of using their PGM FI tech. But it still made 110 bhp and 97 Nm of torque.

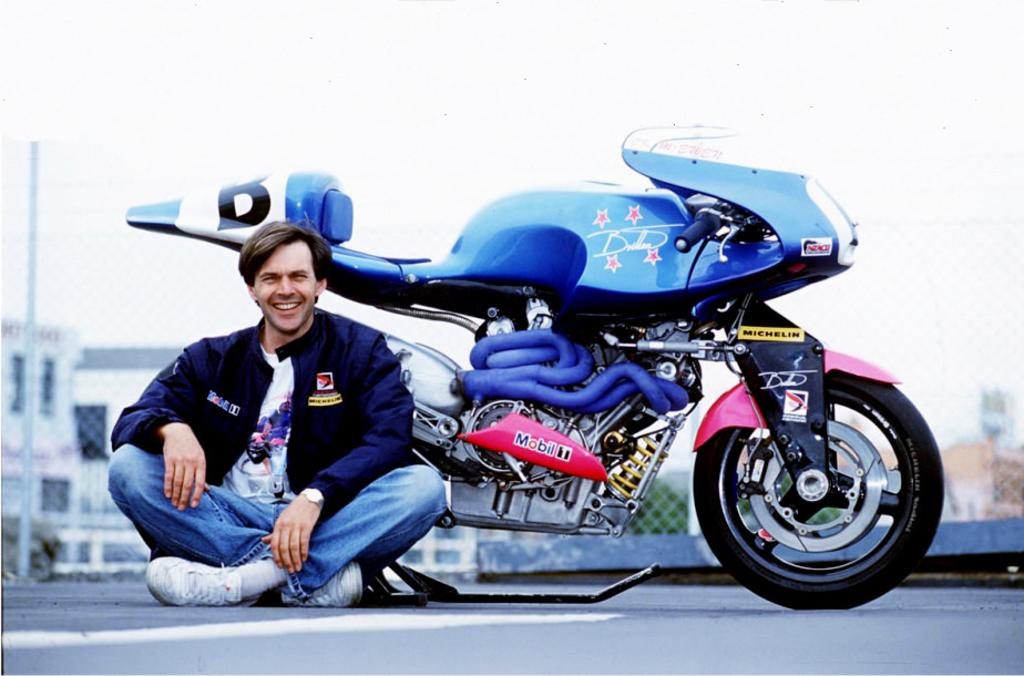

Suzuki TL1000S (1997)

The TL1000S or also called TLS was also another entrant to challenge the Ducati 916.

Its 90-degree V-Twin produced 125 bhp and 105 Nm of torque, making it the most powerful V-Twin sportbike at the time. In fact, the engine was sold to Cagiva and Bimota (to create the SB8K).

However, the engine blocks were long and pushed the engine placement far back into the frame. That would have the effect of elongating the wheelbase. Suzuki engineers had to think creatively and came up with a revolutionary rear suspension set up, which used a separate damper from the spring. It was a technology adopted from Formula 1.

Read more about the TL1000S in 10 Biggest Motorcycling Bungles of All Time.

Bimota V Due (1997)

The world held its collective breath when Bimota announced that they were working on a road legal 500cc two-stroke V-Twin. It was also the company’s first in-house engine, since they sourced all their engines from other manufacturers.

To overcome the pollution innate to two-strokes, Bimota introduced direct fuel injection while 2T was inducted into the crankcase. It produced 105 bhp and 176 kg that would annihilate other sportbikes.

Not so. The fuel injection and oil induction technique didn’t quite work in the real world and the bike suffered inconsistent power delivery and seizures. Owners who couldn’t take it returned the bike to Bimota. Suddenly, they found themselves with a recall of titanic scales for such a small manufacturer.

All their resources went into fixing the bike and bankrupted Bimota.

Still, there were a number of fixed bikes in the market and now in the hands of collectors.

Read more about the V Due in 10 Biggest Motorcycling Bungles of All Time.

Triumph Daytona T595 (1997)

The Daytona T595 was actually a 955cc triple. The name was derived from “T5” engine series and “95” shortened from 955cc. Its name was changed to the Daytona 955i in 1998 due to the confusion among consumers.

The inline-Triple was partly engineered by Lotus. It produced a healthy 128 bhp at the rear wheel and 100 Nm of torque. Along with its superb handling it cemented Triumph’s strategy of using three-cylinder four-stroke engines in the face of the ubiquitous inline-Fours.

BMW R1200C (1997)

The R1200C was BMW Motorrad’s attempt to break into the cruiser market, featuring long front Telelever forks and a foldable passenger seat.

Some liked it, some panned it but it earned a place as one of four BMWs featured in the Art of the Motorcycle exhibition in the Guggenheim Museum.

When production stopped in 2004, BMW vowed to return with a new cruiser in later years. That’s the upcoming R18 at EICMA 2019.

Aprilia RSV Mille (1998)

The RSV Mille marked a turning point for the small Italian sportbike maker. The Mille (means 1000 in Italian) was the first large-capacity Aprilia sportbike.

Most of its innovations were found in the engine. Instead of following the grain with a 90-degree V-Twin, the Mille used a 997cc 60-degree V-Twin made by Rotax. To quell secondary vibrations, counterbalancer shafts were placed in the cylinder heads. Although powerful at 130 bhp and 105 Nm, its fuel injection was smooth.

Many revisions later, the Mille became the RSV4 1000, and now the RSV 1100.

Suzuki TL1000R (1998)

The TL1000R was the fully-faired version of the TL1000S. It was meant for racing and to challenge the Ducati 916 high-water mark. The TLR pretty much unchanged from the TLS, apart form the forged pistons, stronger conrods and stiffer frame. But it weighed 197 kg dry.

It was raced in WSBK and AMA Superbike but achieved only a singular win. Suzuki decided to cancel the TLR racing program and reverted to the lighter and cheaper GSX-R750.

Yamaha YZ400F (1998)

Just when did four-stroke engine become popular in dirt bikes? It’s this one.

As regulations began to clamp down on two-stroke dirt bikes in the USA, Yamaha decided to go ahead with building a four-stroke competition machine to go up against the 250cc two-strokes. Knowing that two-strokes had supremely higher peak horsepower, the YZ400F project leader decided to adopt Yamaha’s Genesis 5-valve superbike head to the the dirt bike. It was also the first bike to feature the awesome Keihin FCR carburettor as stock.

The result was an engine that revved to 11,000 RPM and almost equalling the two-stroke’s. At the same time, the four-stroke engine had better low-end drivability and engine braking.

Yamaha’s decision paid off when Doug Henry rode the prototype YZ400M to victory at an AMA Supercross event in 1997, paving the way for the YZ400F.

Henry won the 1998 AMA National Motocross Championship on the YZ400F. This was the turning point.

Yamaha YZF-R1 (1998)

What else did the motorcycling world remember in 1998 but the R1?

Yamaha, having been beaten soundly by the Honda CBR900RR responded with this bike. The YZF-R1 featured many innovations that were adopted by all manufacturers until today.

First, they “stacked” the gearbox by raising the inout shaft above the output shaft, effectively making the engine a single, compact unit. And since the engine was more compact, it allowed the engineers to reposition it as the centre of gravity (this was the start of unitised mass). The swingarm could also be elongated while keeping the wheelbase short for agility.

The inline-Four engine used Yamaha’s 5-valve-per-cylinder Genesis layout and the EXUP exhaust valve. The EXUP valve gave the engine a much more wider and linear powerband, enabling good low-end torque with high-RPM power. It resulted in a stupendous (at the time) 148.8 bhp and 108.3 Nm of torque.

And, remembering that the CBR900RR became the king because of its low weight, Yamaha engineers dieted the YZF-R1 to weigh only 177 kg dry/192 kg wet.

In testing, the R1 hit 0 to 100 km/h in 2.96 seconds, 0 to 160 km/h in 5.93 seconds, and 400 meter mark in 10.19 seconds at 211.47 km/h. To say that it blew everything else away was an understatement.

Understand that this was a 150 bhp bike when there was no traction control and ABS wasn’t mandated yet!

It was the new benchmark for sportbike performance.

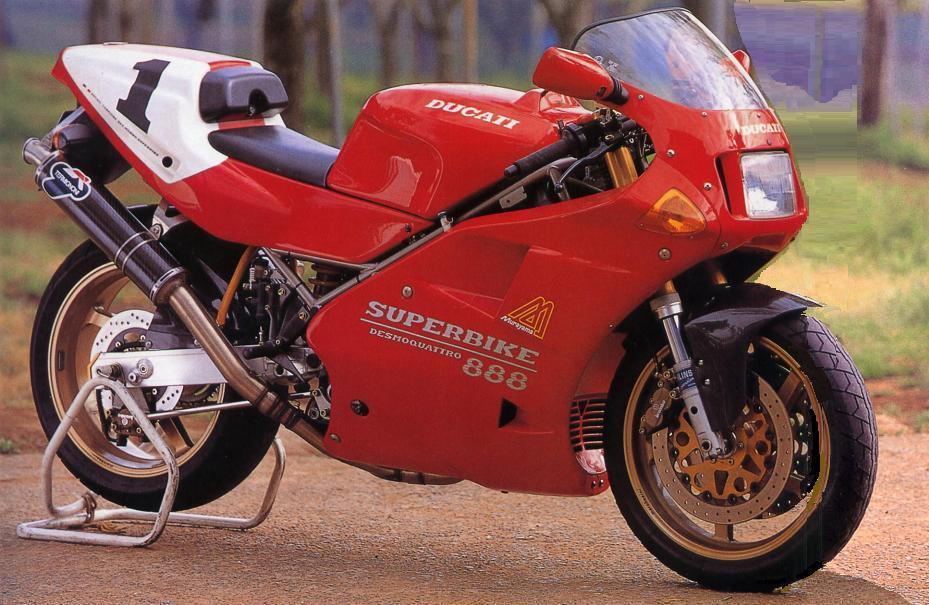

Ducati 996 (1999)

Manufacturers introduced a number of truly great memorable, if not great, bikes as the new millennium approached.

One of them was this, the 996. It was reputed that Ducati made the 996 to compete with the Aprilia Mille. In any case, the 916/955/995/996 was nearing the end of its developmental curve and 2001 would see the introduction of the 998.

The 996 was offered in three models, just like current Ducatis: The base 996 model in the single seat Strada or dual seat Biposto; 996S with Öhlins suspension; and 996SPS for Europe only. The SPS was the WSBK homologation model, featuring titanium and carbon fibre parts. It was succeeded by the 996R in 2001 which used the now-famous Testastretta (narrow head) V-Twin engine.

The SPS’s engine had larger pistons and valves, stronger crankshaft and crankcases. The biggest innovation was the use of two fuel injectors per throttle body. One pair sat lower underneath the butterfly valves, while the extra pair sat above the bell mouths and showered fuel into the throttle body at higher RPMs. The “shower” set up allows fuel to atomise better at high RPM.

Power ranged between 112 bhp in the base and S model to 124 bhp in the SPS model.

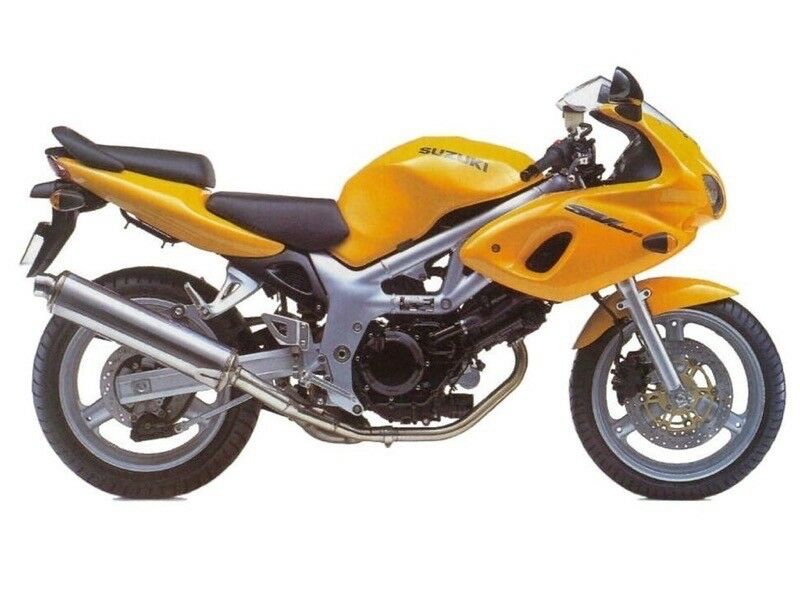

Suzuki SV650 (1999)

The SV650 took the TL1000S/TL1000R V-Twin format to the emerging naked middleweight market. Rather than being a maddeningly powerful bike, the SV650 offered lightweight, a responsive chassis and linear spread of power, thereby endearing itself to new and veteran riders alike.

Although virtually unknown in Malaysia, it continues to sell well in Europe, hence still being in production after 20 years.

Yamaha YZF-R6 (1999)

There were five great superbikes in 1999 including the aforementioned Ducati 996 and this, the YZF-R6.

The R6 was the smaller cousin of the YZF-R1 and just like the R1, it’s made to conquer the 600cc sportbike market. The 16-valve (instead of the 20-valve R1) engine produced 120 bhp at an astronomical 12,000 RPM but just 68 Nm at 11,000 RPM. That made the bike peaky like a two-stroke.

But with a dry weight of only 167.5 kg, it was a thrill to ride.

Yamaha YZF-R7 (1999)

Yamaha also introduced the race homologation YZF-R7 “OW02” in 1999 to replace the ageing YZF750. It was meant as a race bike right out of the box and only 500 were produced.

The stock engine produced 106 bhp and had Öhlins suspension, but the bike cost USD 32,000 (RM 121,600 in 1999 rate). However, there were two race kits available. The first one, which cost USD 914.25 (RM 3,474.15) turned the engine to 135 bhp. The second cost USD 12,190 (RM 46,322) and upped power to a fire-breathing 162 bhp.

The ECU was pre-programmed with the race maps and will identify the type of race kit plugged in.

Although it had limited success in WSBK, it was simply one of the most exotic bikes ever made.

MV Agusta F4 Serie Oro (Gold Series)

The MV Agusta F4 or F3 may look blasé these days, but their styling was the most groundbreaking in 1999. Cagiva had sold Ducati to the Texas Pacific Group in 1996 and concentrated on the MV Agusta brand. Working from the Cagiva Research Centre (CRC), the late-Massimo Tamburini penned the F4 as an evolution to the Ducati 916, and revived the MV brand.

It was actually unveiled at EICMA 2017 but production began in 1999.

Click here to read about What Happened to Cagiva.

The Serie Oro used a magnesium swingarm, wheels and frame sideplates that were anodised in gold. All painted parts as well as the airbox were made of carbon fibre. All these lightweight material kept weight to 181 kg.

Its 16-valve inline-Four engine was one of the very few to use a hemispherical cylinder head cover. Spent gases exited through four exhaust tips under the seat which resembled church organ pipes.

Only 300 were made and each came with a certificate of authenticity as well a 24-karat gold badge etched with the bike’s serial number.

A standard production F4 750 S was also produced, using non-exotic materials.

Suzuki GSX-1300R Hayabusa (1999)

No other bike made more noise in 1999 than the Hayabusa. Designed in the windtunnel with the specific purpose to be the world’s fastest production bike, it featured an appearance that polarised opinion until today.

But it did perform its purpose, becoming the first and only bike to hit 312 km/h. To do it, the engine produced 173 bhp and 138 Nm of torque.

However, it would become the fastest production bike of all time, as a gentlemen’s agreement among manufacturers limited top speeds of future bikes to 299 km/h, regardless of how much power they made.

Click here to read more about the Hayabusa in 15 Fastest Production Motorcycles of All Time.