Please click here for Part 1 (Suzuki RE5), here for Part 2 (Honda CBX1000), here for Part 3 (Yamaha GTS1000), here for Part 4 (Suzuki Katana), here for Part 5 (Böhmerland), here for Part 6 (MTT Y2K and 420RR), here for Part 7 (Honda DN-01), here for Part 8 (BRP Can-Am Spyder), and here for Part 9 (Honda NR).

We’ve reached the final motorcycle in this collection. We’ve decided to leave out the older motorcycles prior to the 80’s and 90’s as they were too far back and most of the successful technologies and methodologies have been transferred to motorcycles in the following decades.

That doesn’t mean manufacturers have stopped researching and developing new ideas. Far from it, in fact. But manufacturers are more in tune to what the majority of potential buyers want these days to design bikes that don’t look totally out of this world, apart from a few.

Without much further ado, let’s check out this last bike.

BIMOTA TESI 3D

Truth is, any Bimota would be considered unusual compared to virtually any stock production bike, but that would mean all ten would be Bimotas in this article. Picking just one out from the Rimini, Italy-based company’s family isn’t easy either, like the 1998 SB8R and SB8 RS, DB3 Mantra.

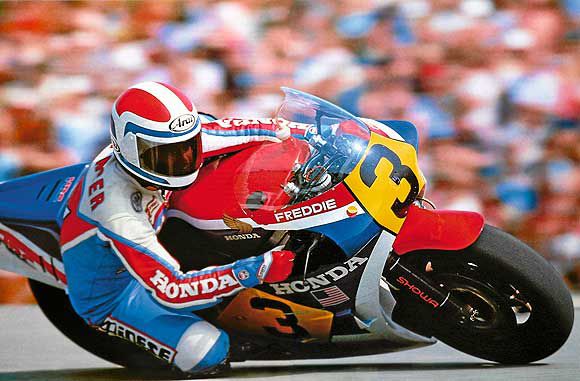

For example, the YB4EI which come agonizingly close to winning the inaugural World Superbike Championship in 1988, ridden by one Davide Tardozzi. Tadozzi had won eight races that season but because of point scoring technicalities, Fred Merkel won on the Honda RC30 despite having just two victories.

Bimota only builds frames, chassis and other technologies around engines from other manufacturers. The first letter of a Bimota denotes where the engine was sourced from, for example: YB means Yamaha-Bimota, BB stands for BMW-Bimota, DB for Ducati-Bimota and so forth. As such, production is low volume. Only the Suzuki GSX-R1100 powered SB6 saw 1,144 bikes being produced from 1994 to 1996, while the next highest figure was just 600 bikes.

As such, one model, in our opinion which truly reflects upon that philosophy is the Tesi 3D which made its first appearance in 2007.

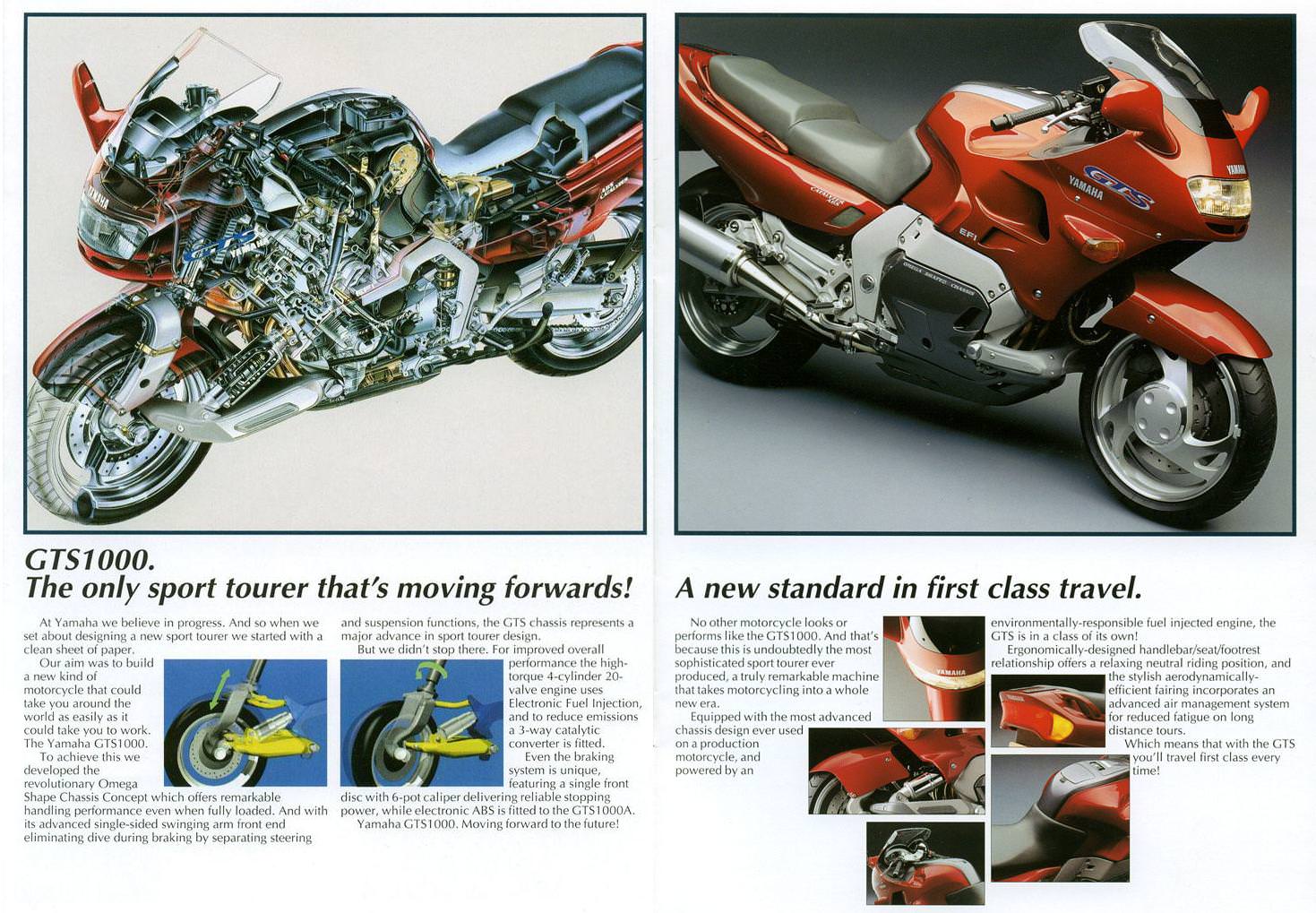

Remember we covered about the attempt to move away from hydraulic forks for the front suspension on the Yamaha GTS in Part 3? The Tesi was also developed in this vein. The concept of the Tesi differs slightly from the Yamaha GTS’s, however.

The Tesi 3D is the third iteration of this project, powered by the powerful Ducati 1098 engine. The engine is clamped between two machines aluminium plates, with all other components mated to these plates, including both front and rear swingarms.

The front swingarm mates to plate on both sides, with an Ohlins shock attached to the right in a cantilevered position. The handlebar’s shaft is connected to horizontal shafts on each side that steers the front wheel, for a hub centre steering setup.

Bimota is currently building the new Tesi 3D to celebrate their 40th year, called the Tesi 3D 40 Anniversario (pictured here). Only 40 examples will ever be built.

BONUS UNUSUAL PRODUCTION MOTORCYCLE

How could we leave out the Kawasaki Ninja H2 and its variants? Unleashed by Kawasaki in 2015 to be the bike to conquer the world, it’s supercharged.

The track-only H2R produces 300 bhp, while the road-legal version pumps out 200 bhp. Kawasaki had just announced the H2 SX and H2 SX SE sport-tourer. Still supercharged but made practical for daily riding and touring. (Please click here to know more about the H2 SX.)

Please click here for Part 1 (Suzuki RE5), here for Part 2 (Honda CBX1000), here for Part 3 (Yamaha GTS1000), here for Part 4 (Suzuki Katana), here for Part 5 (Böhmerland), here for Part 6 (MTT Y2K and 420RR), here for Part 7 (Honda DN-01), here for Part 8 (BRP Can-Am Spyder), and here for Part 9 (Honda NR).